By Tom Wells, associate artist

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #1: Voice

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #3: Dialogue and Scenes

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #4: Making Worlds

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #5: Planning

Hope everyone enjoyed last week’s writing tasks. This week we’re asking a bit more of you. By the end of this workshop, you’ll be ready to have a go at writing a monologue. A beautiful character portrait and a proper story. That’s the goal. But to give you something to get started with, I think it’s a good idea to do a bit of free writing. Like last week, I know, but it’s the best way I can come up with of shaking off things you’re preoccupied with and getting in the right headspace for making stuff up. So. Here goes:

Exercise One

A little reminder of the exercise: you get a word and then just write. And keep writing. Write any thoughts you have connected to that word and see where it takes you. Whatever comes into your head. It doesn’t have to make sense, it doesn’t have to be in sentences, and it doesn’t matter if it ends up having nothing to do with the word you were given to begin with.

The important thing is to keep going. If you don’t know what to write, write about how you don’t know what to write and just see what follows on from that. Something interesting, something funny, something unexpected – anything’s fine. Time yourself doing it. For the first word, keep going for thirty seconds. The first word is: make. Write whatever comes into your head when you think of the word make.

Go.

For the second word, the challenge is to keep going for a minute. The second word is: good.

Go.

And keep going.

For the third word, the challenge is to keep going for two minutes. The third word is: stuff.

Go.

And keep going. And keep going. And stop.

Exercise Two

When I was growing up, my Mum often described stuff as ‘character-building’. Gale-force winds, maths, glandular fever. Things to experience so that afterwards you’re a better-rounded person, with funny stories to tell and a bit more empathy. I think it was good practice for being a playwright too. Character building is a big part of your job.

When you’re building a character it is useful to know as much about that character as you can – their daily lives, their memories, what they sound like and look like and the gestures they make when they’re talking, or not talking, their struggles, their hopes, their favourite phrases, their favourite socks, their childhood toys, their scars and how they got them, and (most importantly) their name.

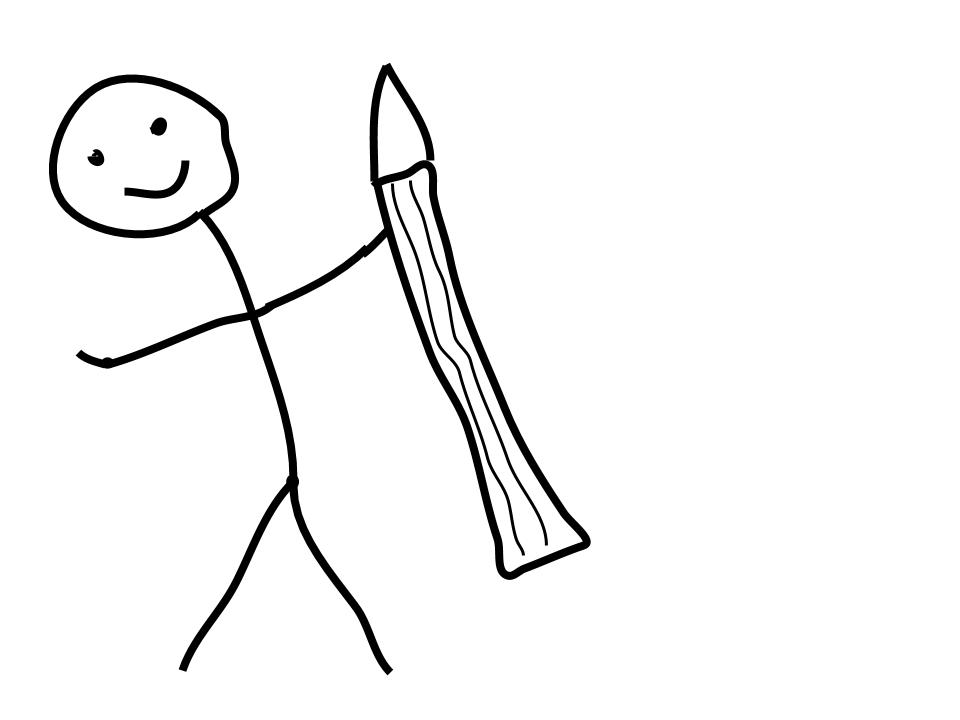

Self Portrait, 2020 by Jamie Potter

This next exercise is about getting to know a character. The sort of person who would say the thing that leapt out at you from your free writing, the thing you’ve written at the top of your piece of paper.

Draw a stick figure version of them. Give them a name, an age. And then write things about them in the space around the drawing. Just anything that comes to you. And label them with the information.

So, for example, if they have a wonky nose or a scar on their chin, write about it, about how they got it, if there’s a story, or what it means for them in the world, if they’re self-conscious about it when they meet new people, or if they’re proud of it maybe. If they’ve got a cardi they always wear, describe it. Or a gesture they always make, or a thing they always say. See if you can write down everything about that character you can think of.

Spend a good bit of time with them – ten minutes, say – getting to know them and writing down the interesting details of their lives. Have a good look at the portrait you’ve drawn of them. And then take this character into the next task.

Exercise Three

You’ve got your character, and spent a bit of time getting to know them. There’s two more things to mention at the start of this exercise.

The first is a straightforward story structure. There’s lots of different models for story structure, and all of them are good to follow and think about and find out about from different playwrights and plays and guides to writing. The one we’re going to base this task on has five different bits, as follows:

- A character wants something, and sets out to get it;

- Things go well – the character manages to get a bit nearer to the thing they want;

- Things start to go badly – the character comes up against obstacles, but keeps going;

- Things go very wrong for the character – it looks like the thing they wanted is out of reach, unachievable;

- Some kind of resolution: maybe the character gets the thing they wanted; maybe the character doesn’t, and has to give up; maybe they get something different, something they need.

This will hopefully help you to give a shape to your monologue.

The second thing to mention is choosing something your character wants. If we were all together in a workshop, we’d do a lucky dip and you’d all choose something from a bag without looking. But, since we’re not, here are a few of the items you might’ve picked:

- a key

- a phone

- some chilli flakes

- a pound coin

- a box of juice

- some painkillers

- a screwdriver

- a stamp

- a condom

- a safety pin

- a Kitkat

Choose one of these things, and imagine a scenario where it is the most important thing your character needs. Then, using the story structure mentioned above for help, write a monologue. Imagine the character you built in Exercise Two sets out to get the thing you chose in Exercise Three.

Write it from the character’s point of view, in their voice and, to make it feel like it is happening as we see it, write it in the present tense. Don’t worry about getting it wrong, just try it. Give yourself fifteen minutes for this task. Once you’re done, read it through and feel a bit proud.

Homework

The monologues you end up writing for Exercise Three will probably be a mixture of brilliant bits and messy bits. It’s your first draft of your first go, under time pressure, with things that were out of your control, and you’re only just getting to know the character, just starting to hear their voice a bit. But hopefully now you’ve had a go with a quickly-made-up character and a lucky dip thing-they-want, you’ve got the skills to write something a bit more considered. If you fancy doing a bit of homework, this might be a good task:

Think about a character you’re really drawn to writing. Do a portrait of them – just a stick drawing, but labelled with their quirks and memories and appearance and gestures and phrases they use a lot. Spend a bit of time getting to know them. Try to hear the way they sound, the words and phrases they use, the rhythms of their speech.

Now think of the thing they want most, more than anything else, in the moment that your monologue will start. It might be something grand and abstract, like love, or justice, or freedom. It might be something a bit more everyday, like a yogurt. But make sure it comes from what you know about the character. And then, following the story structure given above as a guide, imagine the character setting out to try and get the thing they want the most in the world at that moment. What things might get in the way? Do they manage in the end? Have a go at writing this monologue.

Feel free to share your writing with us on social media: simply tag @middlechildhull on either Twitter, Instagram or Facebook.

- Playwriting with Tom Wells #3: Dialogue and Scenes

This is a really good thing to put online at this particular time!